About the Author

Dr. Ed Gamboa, MD, FACS

Dr. Ed Gamboa is a hundred percent Bisaya. Second of nine children of Cebuanos, Atty. Pedro C. Gamboa and Inocencia Gamboa, and delivered at the Leyson Clinic at Jakosalem and P.del Rosario by Dr. Macrina Leyson, he was baptized by Msgr. Gabriel Reyes at the Archbishop's Palace. Like many kids from the city, Ed often spent his weekends by the beaches of Talisay and Mactan. During the summer, he traveled to Bantayan (his grandfather Primo's town) and the adjacent islands of Cebu, if not enjoying the string of movies in Colon or serving Latin Mass at the Redemptorist church.

Ed attended kindergarten at Colegio Inmaculada Concepcion (1955), under Sor Salvacion; elementary at University of Southern Philippines, under Principal Rosario Liao Lamco, Mr. Comendador, Mrs. Dinsay and Mrs. Pahang; high school and college at Seminario de San Carlos in Mabolo, under Frs. Hernandez, Dosado, Lucena, Fuentes, Lamela, Bernal, Presa, Prado, and Blasquez; pre-med at Velez College under Miss Jumalon and medical school at Cebu Institute of Medicine (1970-74) in Ramos, under Drs. Jesus Alvarez, Florentino Solon, Tomas Hernandez, Santos, Camomot, and Jose Paradela.

Happily married to Cebuana Dr. Lucie Escano Noel in 1976, Ed migrated (four years after the imposition of Martial Law) to the United States for specialty training in General Surgery and Pediatric Surgery in New York, and Transplant Surgery in San Diego, while Lucie specialized in Pediatrics and Pediatric Nephrology in New York. Board Certified in Surgery, and a fellow of the American College of Surgeons and the International College of Surgeons, Ed is currently Chief of Surgery at El Centro Regional Medical Center.

Ed and Lucie have four children. Peter-Gabriel is Operations Manager at OCZ Techonology in Silicon Valley and Michael Joseph is in investment banking at Needham in Menlo Park. Lauren Marie is a junior at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana and John Paul is a freshman at College of the Holy Cross in Boston.

Author of "From Mt. Krizevac to Mt. Carmel: A Medjugorje Pilgrim's Conversion", Ed writes a weekly column for the Asian Journal in San Diego (asianjournalusa.com). His second book "Fourteen Virtues of Compassionate Healers" is due for release this year by St. Anthony Messenger Press.

It started with an email of nostalgic pictures culled from the 1950s --- WW II toy soldiers from Kellogg's Corn Flakes boxes, 45 RPM records, Studebakers, 15 cent McDonald hamburgers and 5 cent Coca-Colas, Brownie cameras and aluminum Christmas trees, etc., with the daunting remark: "If you can remember these, you have lived!" To which those who regularly avail of senior discounts at Denny's and movie theatres resoundingly responded in the affirmative.

Not without a hint of cynicism, my brother Robert commented that none of the above qualifies one "to have lived" more than having your frail chest and back greased with hot coconut oil and plastered with gabi leaves to get rid of "panuhot", the all-encompassing diagnosis for childhood ailments. Which commentary in turn initiated a flurry of emails regarding native Philippine remedies.

Medicine in the 1950s was not exactly that primitive. Growing up in Cebu City, the "Queen City of the South", there were excellent family doctors and pediatricians to go to when we got sick. I remember my father bringing me very early in the morning to the residence of Dr. Ramon Arcenas on several occasions.

The manghihilot of Consolacion was a gentle middle-aged Cebuano. He held clinic in the basement of his nipa hut, which was larger than the average bahay kubo. We usually arrived at midmorning. Typically, one of us would wake up with a fever or a hacking cough. My mother would then telephone the school to inform the teacher we would be absent, and then she would arrange for the driver to transport us to Consolacion.

By 9 or 10 AM, the waiting room would be packed; several patients would be standing outside. There was no receptionist. As soon as you arrived, you picked a number fashioned out of tansan (Coca-Cola or Pepsi tops hammered flat and engraved -- by tiniltil method -- with numerals) and awaited your turn. Speaking of tansans, you could, if you planned on going Christmas caroling, nail stacks of tansans together to a piece of wood and enjoy your own handmade percussion instrument.

When your number was called, you were led into the examining room. Dr. Consolacion -- my anesthesiologist brother Alan remembers patients calling him Nong Aurelio -- would take a brief history ("how long has the child been sick?", "did he fall down the stairs?", "has he been vomiting?"), then he would gently place his hands on your chest and back, close his eyes, and say a brief prayer.

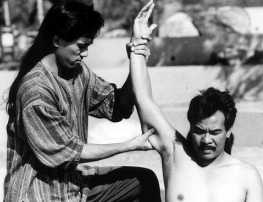

Nodding his head, Nong Aurelio would sit back and tell your parent(s): "Your child has panuhot or lisa (sprain)... he must have fallen down a flight of steps". He then poured warm (or hot) globs of thick, greasy coconut oil on his hands and rubbed your chest and back to exorcise your illness, while reciting more prayers.

Soon, the dreaded moment came. Nong Aurelio would summon his "physician assistant" who promptly lifted and carried you on his back, rocking you back and forth to stretch your spine and hips. After the judo-like routine, the muscular medical assistant would grab you by the ears, lift you clean off the ground, and sway you back and forth until your neck cracked. Luckily, none of us ever got paralyzed!

Then it was back to the manghihilot's examining chair for more goops of oil. Taking a handful of gabi leaves stacked by his side, Nong Aurelio would run them over a lantern flame, toasting them ever so slightly, before plastering them against your chest and back. I guess the idea was to keep the oil from evaporating too quickly and to use whatever medical properties the leaves had.

We would thank Dr. Consolacion and leave money in a donation box. He never charged for anything. That would have risked losing the healing powers God gave him. There were no insurance papers to fill, no billing claim to be sent, no co-pay. There were no middle managers, no HMO authorization process, and no bureaucracy whatsoever. Native medicine was purely a sacred traditional relationship between the healer and the sick.

The best part for me was going home tired and sleepy (from the long 12 kilometer car ride), and going to bed with the latest DC Comics copy of Superman or Batman (one of the perks of getting sick) and sipping a glass of Welch's grape juice or 7-up. We had the choice of keeping the gabi leaves stuck to our bodies the rest of the day or my mother would peel them off and exchanged them for tinastas nga panapton (pieces of cloth left over from her sewing chores) caked with pink yucky Numotozine.

Dr. Consolacion's ICD list of diagnoses was limited to "panuhot" (strained muscle or air trapped in body cavities) or lisa (strained joint). Likewise, therapeutic measures were confined to coconut oil, gabi leaves, and prayer. But, somehow, sick children got better....and survived to adulthood (all my eight siblings are alive and well, thank God). Luckily, no one got paralyzed from the vigorous physical therapy. Bottom line is: we were cured.

I did hear many years later that none of Nong Aurelio's kids took over his "hilot" practice. They all became either physicians or nurses.

The native treatments that I witnessed (or received) growing up in Cebu, whether administered by albularyo or manghihilot, fascinate me because they must have somehow worked, otherwise why would people return for treatment? Viewed now from the perspective of modern science, many of the indigenous or antique therapeutics look more like placebos. But they were readily available, arguably effective, and definitely affordable or, for the most part, free.

The term albularyo derived from the Spanish herbolario (herbalist). Albularyos are general practice healers who take care of common illnesses such as fever, cough, cold, diarrhea, etc. using medicinal herbs, which rural area folks commonly stock in their medicine cabinets. Albularyos also take care of people believed to be afflicted by supernatural illness or witchcraft. Thus their medical repertoire, in addition to herbs, includes chants, prayers, icons and religious articles.

The manghihilot is a more specialized medicine man or woman, focusing on musculoskeletal problems, much like chiropractors. They use massage techniques utilizing oil and salves to cure panuhot (strained muscle or air trapped in body cavities) or lisa (sprained joint). Some of the modern manghihilots have incorporated reflexology and acupuncture mapping into their practice.

In addition to the albularyo and the manghihilot, other native healers include midwives (mananabang in Bisaya, magpapaanak in Tagalog), the mangluluop, manghihila, mangtatawas, mediko, faith healers, etc. Medikos or medicos supplement native therapeutics with Western pharmacology. Filipino faith healers have, in some cases, achieved international fame (or notoriety) and, in some ways, are the pioneers of medical tourism.

There are about two dozen scientifically recognized medical herbs and plants in the Philippines. Boiled ginger to soothe sore throat is fairly well known. In fact, the concoction is now commercially available in powdered form or ginger tea (salabat).

A mixture of sampalok or sambag (tamarind), luy-a (ginger), and calamansi or lemoncito (citrus) works well for cough. Avocado, guava, and star apple (kaimito) leaves are the local version of Lomotil or Loperamide (Imodium). My mother used to heat rice grains until they turned brown, then added water to make an anti-diarrhea drink.

My sister Daisy, when pregnant with her first child, was advised by my aunt, who bore eleven healthy children, to boil thirteen kinds of roots and drink the bitter brew to ensure an uncomplicated delivery. She faithfully followed the time-tested advice but got so sick with the brew’s aftertaste that she no longer cared if she had a difficult labor. Those were the days before epidural anesthesia became common practice.

Talking about nasty medicines, cod liver oil in the form of Scott’s Emulsion was a popular source of multivitamins A and D, calcium, phosphorus and omega 3. I cringed every time my turn came to swallow two full tablespoons of the awful syrup. I'm amused to learn that Scott’s Emulsion is still available in some drugstores in the United States, and remains popular in Mexico, Central and South America, Asia, Africa, etc. My sympathy goes to those kids whose daily dose of vitamins emanate from that nasty brown bottle.

Raw eggs (with the attendant risk of Salmonella infection) blended in milk or Tru-Orange was not as nasty as Scott’s was but why did people think the frothy potion was helpful for hangovers? Was there credible research that showed that the eggnog mix protected alcoholics from developing liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension?

Lately, the popularity of Tawa-Tawa usage for Dengue fever is supported by government health agencies. Research has reportedly confirmed the common plant's antiviral and antibacterial properties. Tawa-Tawa is believed to help sustain platelets and counter hemorrhagic dengue. Two dozen plants boiled in seven glasses of water, from a report I've read, is the current recommended dosage

Gumamela or Hibiscus, also boiled in water, may be applied as poultice to inflamed wounds or abscesses. Some claim the flower has varied uses for cough, fever, hypertension, urinary tract infection, etc. But have you heard of inhaling adobo to get rid of your cold? Not sure about that one. Inhaling Vicks Vaporub dropped in steaming hot water may work, however. You can maximize the effects of such treatment by capturing vaporized oil with a large tent-like cape or blanket draped over your head.

Boiled guava leaves, particularly leaf sprouts, make excellent salve for new mothers, as effective as TUCKS Witchazel pads. Its topical application extends to those who suffer from inflamed hemorrhoids. Before Hibiclens and Bacitracin became commercially available, warm water blended with guava leaf extracts were used to cleanse nuka (Staphylococcal skin infection) so prevalent in children.

As beneficiaries or practitioners of modern Western medicine, we may tend to dismiss many of these primitive therapies as ineffective or unscientific. Yet, we may recall that back in the 5th century BC, Hippocrates, the father of medicine, wrote about a bitter powder extracted from the bark of the willow tree that relieved pain and reduced fever. Knowledge about the analgesic willow tree survived through the centuries.

In 1853, the French chemist Charles Frederic Gerhardt synthesized acetylsalicylic acid and in 1859, von Gilm purified it. In 1897, Felix Hoffmann, a chemist at Friedrich Bayer and Co., refined the process so that he could administer aspirin tablets to his father who suffered from severe arthritis. The rest, as they say, is history.